Several Wetherspoon pubs have ‘moon’ in their name, linking them with George Orwell’s ideal pub. The famous writer called his fictitious pub ‘Moon Under Water’. This one stands on the site of Allen’s Grocery and Tallow Chandlery Stores. It was demolished in c1885 to make way for a purpose-built post office which served Boston until 1907. For many years, it was Brenner’s Bazaar – then, later, government offices, a restaurant and a bar.

Illustrations and text about the ‘Boston Stump’

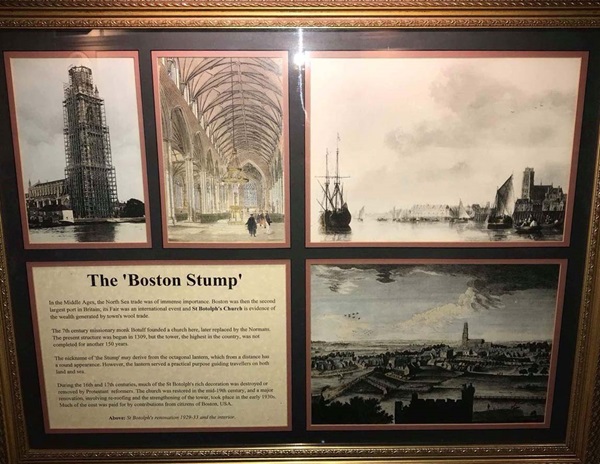

The text reads: In the Middle Ages, the North Sea trade was of immense importance. Boston was then the second largest port in Britain; its fair was an international event and St Botolph’s Church is evidence of the wealth generated by the town’s wool trade.

The 7th century missionary monk Botulf founded a church here, later replaced by the Normans. The present structure was begun in 1309, but the tower, the highest in the country, was not completed for another 150 years.

The nickname of ‘the Stump’ may derive from the octagonal lantern, which from a distance has a round appearance. However, the lantern served a practical purpose guiding travellers on both land and sea.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, much of the St Botolph’s rich decoration was destroyed or removed by Protestant reformers. The church was restored in the mid 19th century, and a major renovation, involving re-roofing and the strengthening of the tower, took place in the early 1930s. Much of the cost was paid for by contributions from citizens of Boston, USA.

Above: St Botolph’s renovation 1929-33 and the interior.

Prints and text about Jean Ingelow

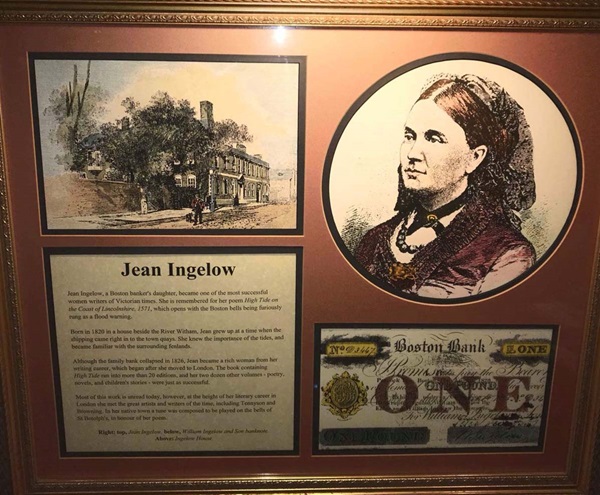

The text reads: Jean Ingelow, a Boston banker’s daughter, became one of the most successful woman writers of Victorian times. She is remembered for her poem High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire, 1571, which opens with the Boston bells being furiously rung as a flood warning.

Born in 1820 in a house beside the River Witham, Jean grew up at a time when the shipping came right to the town quays. She knew the importance of the tides and became familiar with the surrounding fenlands.

Although the family bank collapsed in 1826, Jean became a rich woman from her writing career, which began after she moved to London. The book containing High Tide ran into more than 20 editions, and her two dozen other volumes – poetry, novels, and children’s stories – were just as successful.

Most of this work is unread today; however, at the height of her literary career in London she met the great artists and writers of the time, including Tennyson and Browning. In her native town a tune was composed to be played on the bells of St Botolph’s, in honour of her poem.

Right: top, Jean Ingelow, below, William Ingelow and Son banknote

Above: Ingelow House.

An illustration and text about John Foxe.

The text reads: Born in Boston in 1517, John Foxe was raised as a member of the Church, then ruled over by the Pope. Foxe went to study at Oxford University when he was 16, and became sympathetic to the Protestant movement. However, he and his friend, the Boston born composer John Taverner, were accused of heresy and expelled.

At that time there was growing criticism of the corruption of the Church. John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible into English allowed people to compare the conduct of the Church authorities with that of its founder. The writings of the Swiss church reformer Martin Luther had also recently appeared.

Foxe became a tutor, and began his best-known work, Acts and Monuments. Popularly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, it told of persecution of English Protestant martyrs during the previous 200 years, and was illustrated with graphic woodcuts.

When the Catholic Queen Mary (or ‘Bloody Mary’) came to the throne, Foxe fled abroad. Parts of his book were published, in Latin, in both Strasbourg and Basel. The work first appeared in English in 1563, after Mary’s death, when Foxe returned to England.

The Book od Martyrs was a huge success, only exceeded by the Bible. It had a profound impact on the English Protestant outlook, but encouraged anti-Catholic feeling for years afterwards. A first edition of the book is in Saint Rodolph’s Church Library, Boston.

Top: Mary Queen of Scott’s and Philip II of Spain

Left: John Foxe

Above: John Foxe’s birthplace

Far left: top, John Wycliffe, below, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

Prints and text about the Pilgrim Fathers.

The text reads: On the outskirts of Boston at Scotia Creek, Fishtoft, stands the Pilgrim Fathers’ Memorial, erected by Boston council in 1957. It was from there, 350 years earlier, that a group of nonconformists first tried to emigrate in search of religious freedom. They intended to go to Holland, but were betrayed to the authorities by the ship’s captain. At that time emigration without permission was illegal.

Seven ‘ringleaders’ were imprisoned and tried in Boston’s Guildhall, before being send back to their villages. A later attempt to sail from the Humber was successful, and the group lived for ten years in Leyden. In 1620, they returned to Plymouth Harbour to sail for the New World in the Mayflower, partly paid for by sympathisers in Boston.

About 100 Pilgrims spent two months at sea in the Mayflower before arriving in New England. By the time the ship left to return to Britain, disease and hunger had halved their numbers. However, as the persecution of Puritans continued, over 80,000 more had left for America by 1640. These included many residents of Boston. In 1630, a group of about 250 sailed from Southampton, aboard the Arbella. The vicar of St Botlph’s, the influential preacher John Cotton, followed three years later became vicar in Boston, USA.

Left: John Cotton Above: The Pilgrim Fathers preparing to embark.

Text about Sir Joseph Banks

The text reads: The naturalist and explorer Joseph Banks inherited his grandfather’s estate at Revesby, a few miles north of Boston, in 1761, at the age of 18. From an early age he had a particular interest in botany, and undertook his first plant-collecting expedition, to Iceland and Newfoundland, in 1766.

Five years later, he accompanied Captain Cook on his three year voyage of discovery round the world in the Endeavour, which he had equipped at his own expense. Banks brought back nearly 4,000 plant species, a third of them new to science.

So many came from one Australian inlet that Cook named it Botany Bay.

Having been elected a fellow of the Royal Society at the early age of 23, he became its president 12 years later, an office he held until the year of his death. He was also appointed scientific adviser to the newly established Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew.

Banks was also recorder of Boston from 1809 until 1820, and the Town Corporation commissioned the portrait which hangs in the Guildhall Council Chamber. Under the tower of St Botolph’s is a memorial tablet recording the names of Banks and other local men, such as George Bass and Matthew Flinders, who took part in the early exploration of Australia.

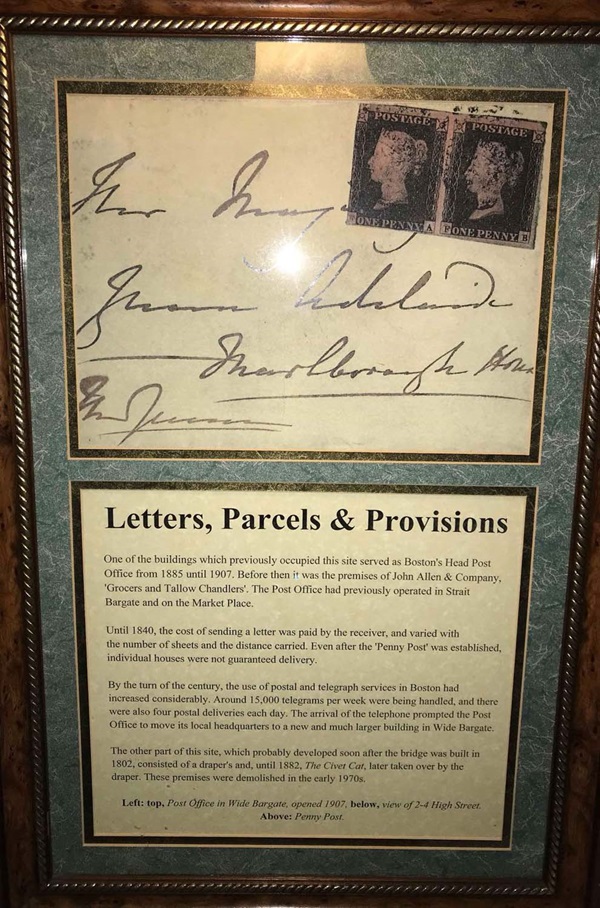

Text about the history of Boston Post Office

The text reads: One of the buildings which previously occupied this site served as Boston’s head Post Office from 1885 until 1907. Before then it was the premises of John Allen & Company, Grocers and Tallow Chandlers. The post office had previously operated in Strait Bargate and on the Market Place.

Until 1840, the cost of sending a letter was paid by the receiver, and varied with the number of sheets and distance carried. Even after the ‘Penny Post’ was established, individual houses were not guaranteed delivery.

By the turn of the century, the use of postal and telegraph services in Boston had increased considerably. Around 15,000 telegrams per week were handled, and there were also four postal deliveries each day. The arrival of the telephone prompted the post office to move its local headquarters to a new and much larger building in Wide Bargate.

The other part of this site, which probably developed soon after the bridge was built in 1802, consisted of a draper’s and, until 1882, The Civet Cat, later taken over by the draper. These premises were demolished in the early 1970s.

Left: top, post office in Wide Bargate, opened 1907, below, view of 2-4 High Street

Above: Penny Post.

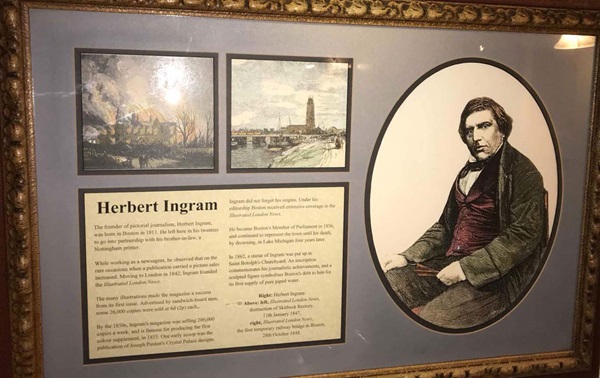

Illustrations and text about Herbert Ingram.

The text reads: The founder of pictorial journalism, Herbert Ingram, was born in Boston in 1811. He left here in his twenties to go into partnership with his brother-in-law, a Nottingham printer.

While working as a newsagent, he observed that on the rare occasions when a publication carried picture sales increased. Moving to London in 1842. Ingram founded the Illustrated London News.

The many illustrations made the magazine a success from its first issue. Advertised by sandwich- board men, some 26,000 copies were sold at 6d (2p) each.

By the 1850s, Ingram magazine was selling 200,000 copies a week, and is famous for producing the first colour supplement, in 1855. On early scoop was the publication of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace designs.

Ingram did not forget his origins. Under his editorship Boston received extensive coverage in the Illustration London News.

He became Boston’s Member of Parliament in 1856, and continued to represent the town until his death, by drowning, in Lake Michigan four years later.

In 1862, a statue of Ingram was put up in Saint Botolph’s Churchyard. An inscription commemorates his journalistic achievements, and a sculpted figure symbolises Boston’s debt to him for its first supply of pure pipes water.

Right: Herbert Ingram

Above: left, Illustrated London News, destruction of Skirbeck Rectory, 11 January 1847, right, Illustrated London News, the first temporary railway bridge in Boston, 28 October 1848.

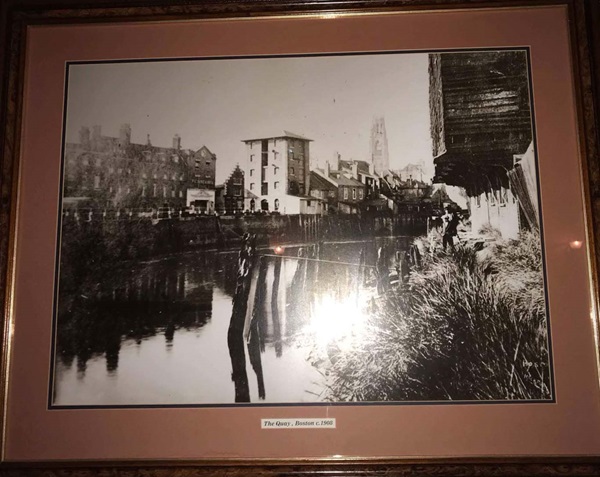

A photograph of the quay, Boston, c1908.

A photograph of the War Memorial and Boston Stump, c1950.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk