Swan Island, 2–4 King Street, Hammersmith, London, W6 0QA

This is named after the famous designer, craftsman, writer and socialist who lived at Kelmscott House, Hammersmith, from 1878 until his death in 1896.

A framed photograph of Morris’s daughter May and her husband Henry Halliday Sparling. Henry was the first Secretary of the Kelmscott Press until he and May separated in 1894.

A framed photograph of Morris’s pressman at Kelmscott Press printing the Chaucer.

A framed photograph of William and May Morris (seated, centre) with the workers at the Kelmscott Press.

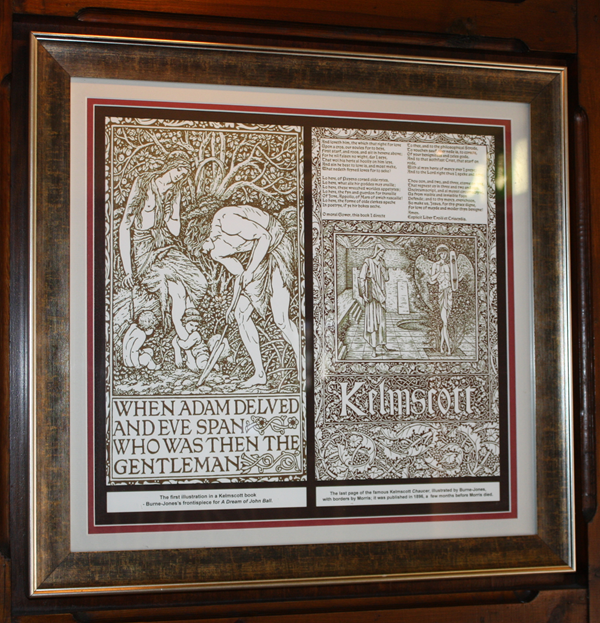

Framed historical illustrations.

The illustrations are captioned (left): The first illustration in a Kelmscott book – Burne-Jones’s frontispiece for A Dream of John Ball; (right) The last page of the famous Kelmscott Chaucer, illustrated by Burne-Jones, with borders by Morris; it was published in 1896, a few months before Morris died.

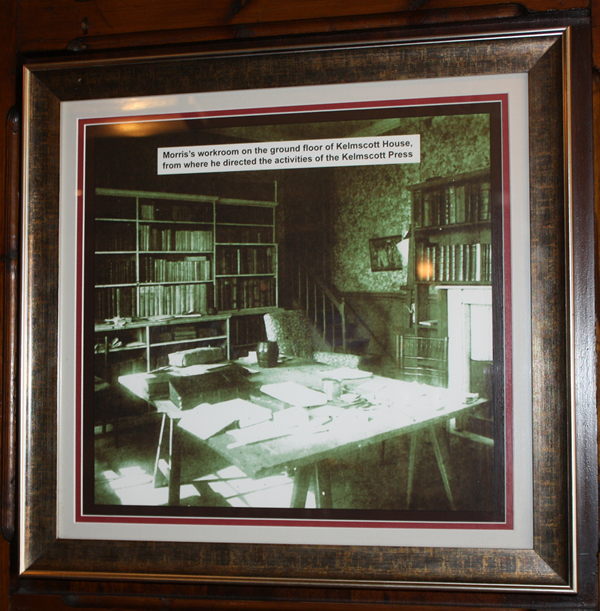

A framed photograph of Morris’s workroom on the ground floor of Kelmscott House, from where he directed the activities of the Kelmscott Press.

A framed photograph of Kelmscott House, Hammersmith, William Morris’s home for the last eighteen years of his life, from 1878 – 1896.

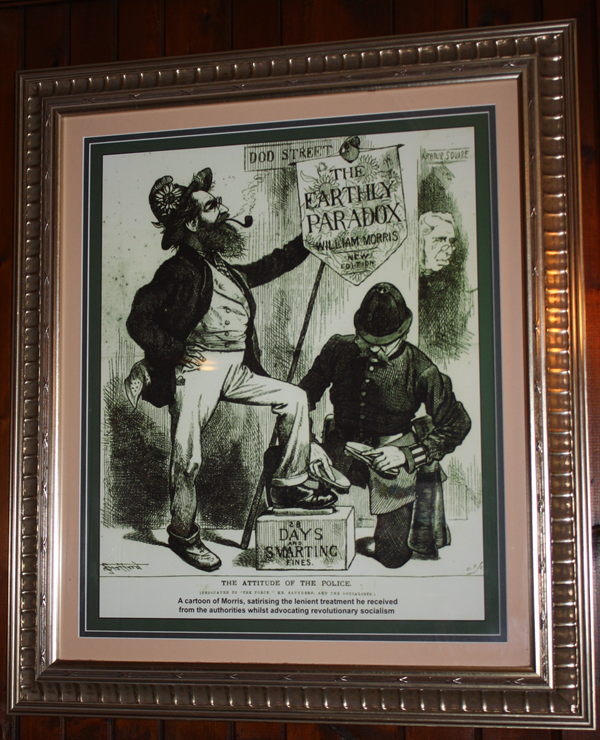

A framed cartoon of Morris, satirising the lenient treatment he received from the authorities whilst advocating revolutionary socialism.

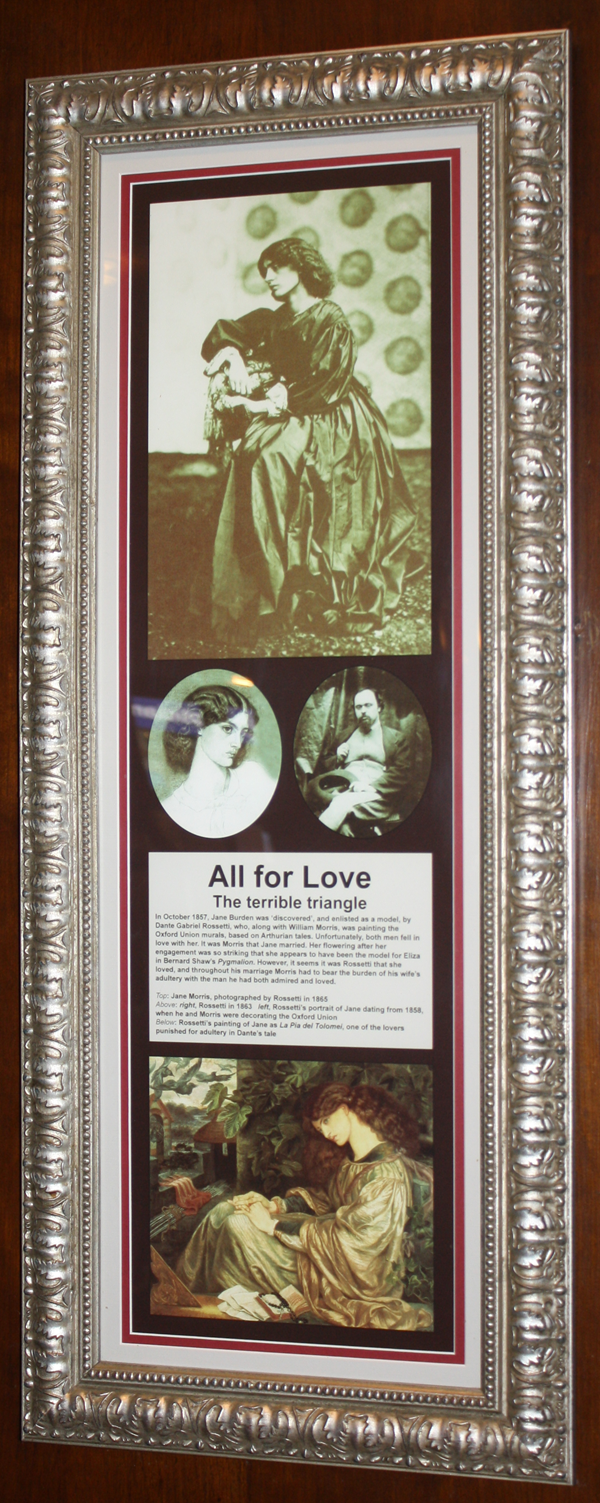

A framed collection of illustrations, photographs and text about the terrible love triangle.

The text reads: In October 1857, jane Burden was ‘discovered’, and enlisted as a model, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who, along with William Morris, was painting the Oxford Union murals, based on Arthurian tales. Unfortunately, both men fell in love with her. It was Morris that Jane married. Her flowering after her engagement was so striking that she appears to have been the model for Eliza in Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. However, it seems it was Rossetti that she loved, and throughout his marriage Morris had to bear the burden of his wife’s adultery with the man he had both admired and loved.

Top: Jane Morris, photographed by Rossetti in 1865

Above: right, Rossetti in 1863 left, Rossetti’s portrait of Jane dating from 1858, when he and Morris were decorating the Oxford Union

Below: Rossetti’s painting of Jane as La Pia del Tolomei, one of the lovers punished for adultery in Dante’s tale.

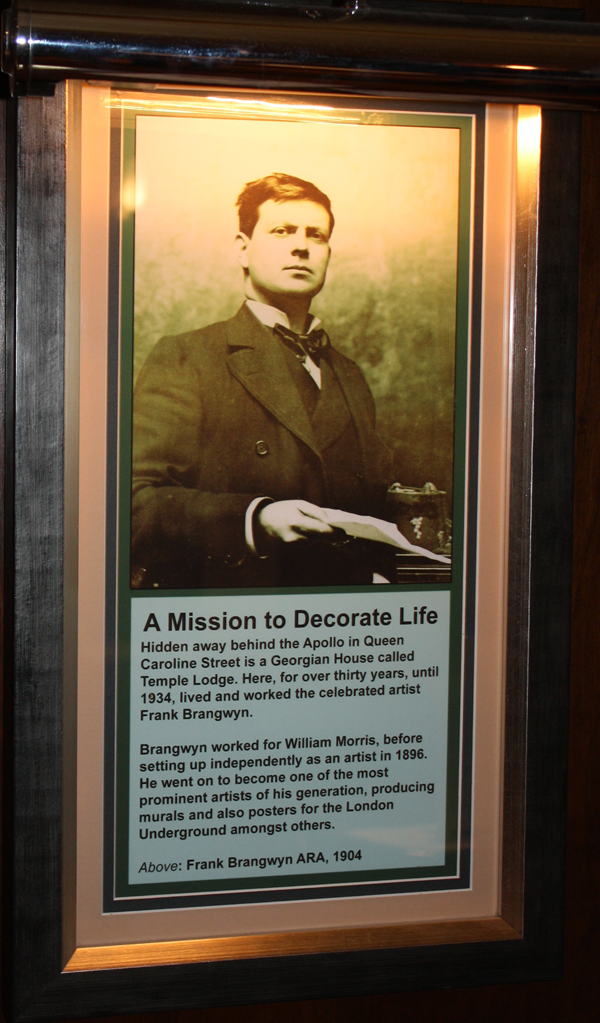

A framed photograph and text about Frank Brangwyn.

The text reads: Hidden away behind the Apollo in Queen Caroline Street is a Georgian House called Temple Lodge. Here, for over thirty years, until 1934, lived and worked the celebrated artist Frank Brangwyn.

Brangwyn worked for William Morris, before setting up independently as an artist in 1896. He went on to become one of the most prominent artists of his generation, producing murals and also posters for the London Underground amongst others.

Above: Frank Brangwyn ARA, 1904.

A framed photograph of Frank Brangwyn at work on his House of Lords murals for the Royal Gallery, as a memorial to the Fallen in the 1914-18 War (they were rejected once finished, and never seen in their intended setting).

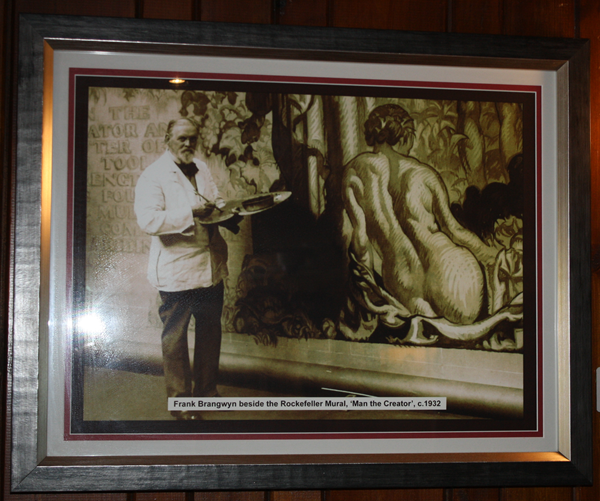

A framed photograph of Frank Brangwyn beside the Rockefeller Mural, Man the Creator, c1932.

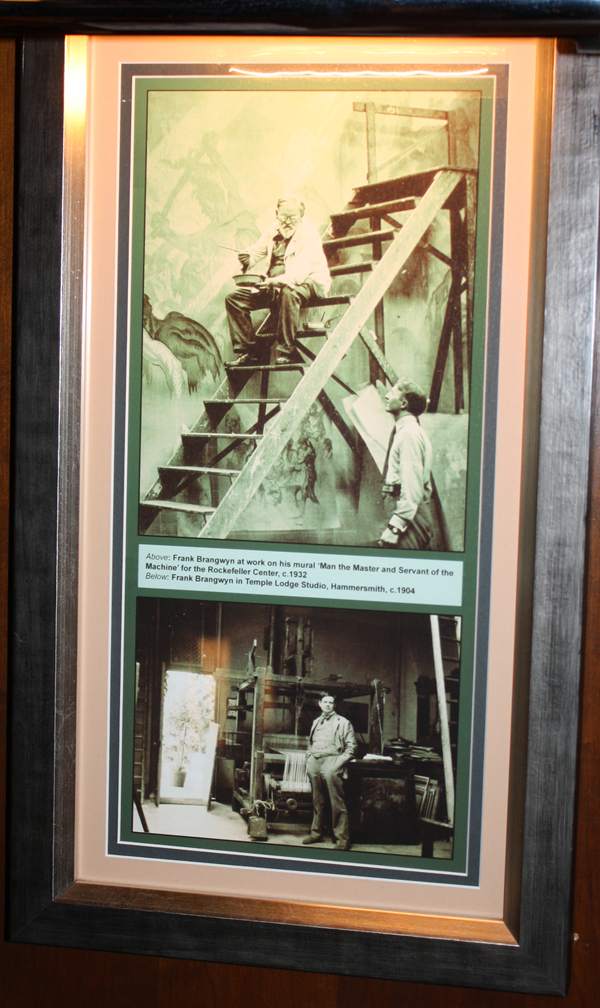

Framed photographs of Frank Brangwyn at work.

Above: Frank Brangwyn at work on his mural ‘Man the Master and Servant of the Machine’ for the Rockefeller Centre, c. 1932

Below: Frank Brangwyn in Temple Lodge Studio, Hammersmith, c. 1904.

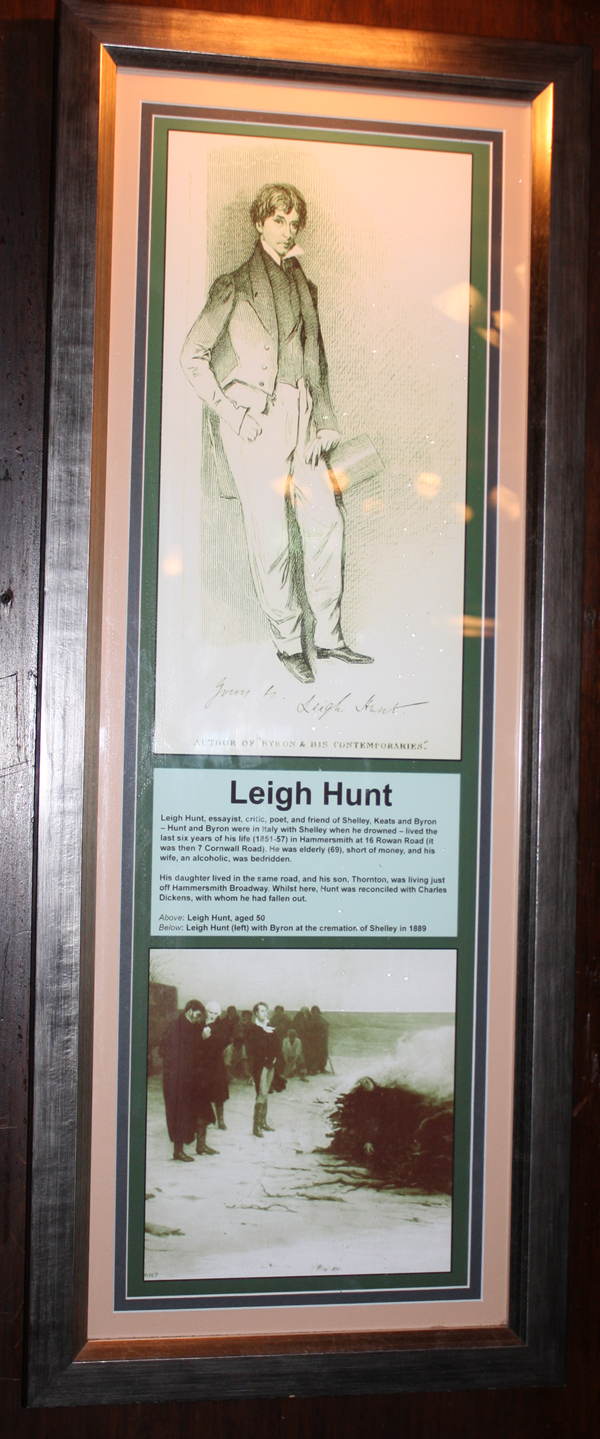

Framed illustrations and text about Leigh Hunt.

The text reads: Leigh hunt, essayist, critic, poet, and friend of Shelley, Keats and Byron – Hunt and Byron were in Italy with Shelly when he drowned – lived the last six years of his life (1851-57) in Hammersmith at 16 Rowan Road (it was then 7 Cornwall Road). He was elderly (69), short of money, and his wife, an alcoholic, was bedridden.

His daughter lived in the same road, and his son, Thornton, was living just off Hammersmith Broadway. Whilst here, Hunt was reconciled with Charles Dickens, with whom he had fallen out.

Above: Leigh Hunt, aged 50

Below: Leigh Hunt (left) with Byron at the cremation of Shelley in 1889

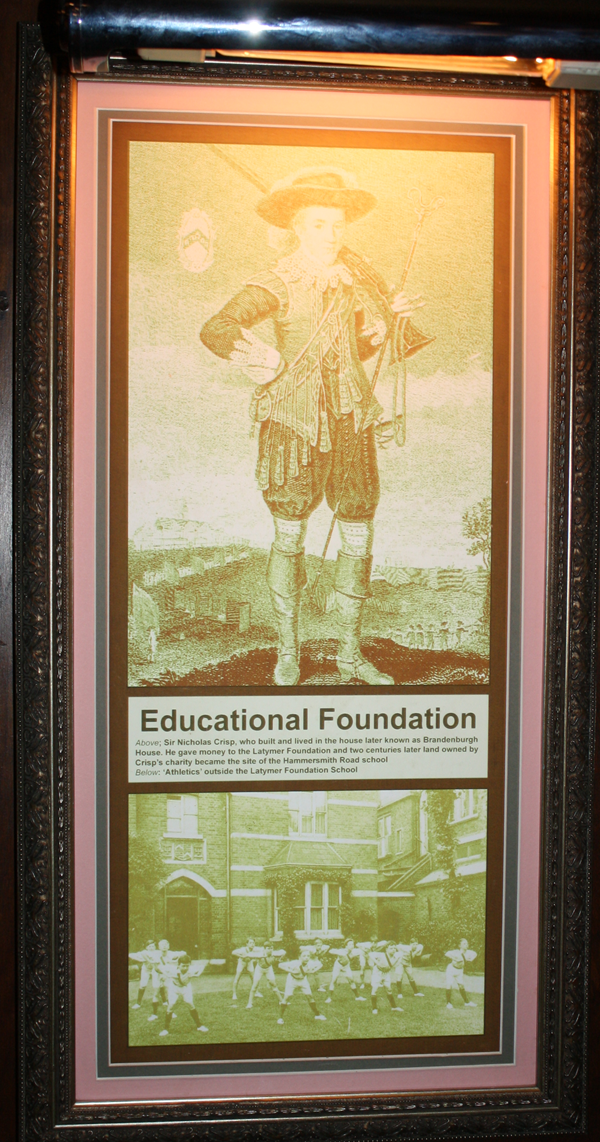

A framed illustration and photograph about education in Hammersmith.

Above: Sir Nicholas Crisp, who built and lived in the house later known as Brandenburgh House. He gave money to the Latymer Foundation and two centuries later land owned by Crisp’s charity became the site of the Hammersmith Road school

Below: ‘Athletics’ outside the Latymer Foundation School.

A framed poster of The Lyric Opera House playbill, 1903.

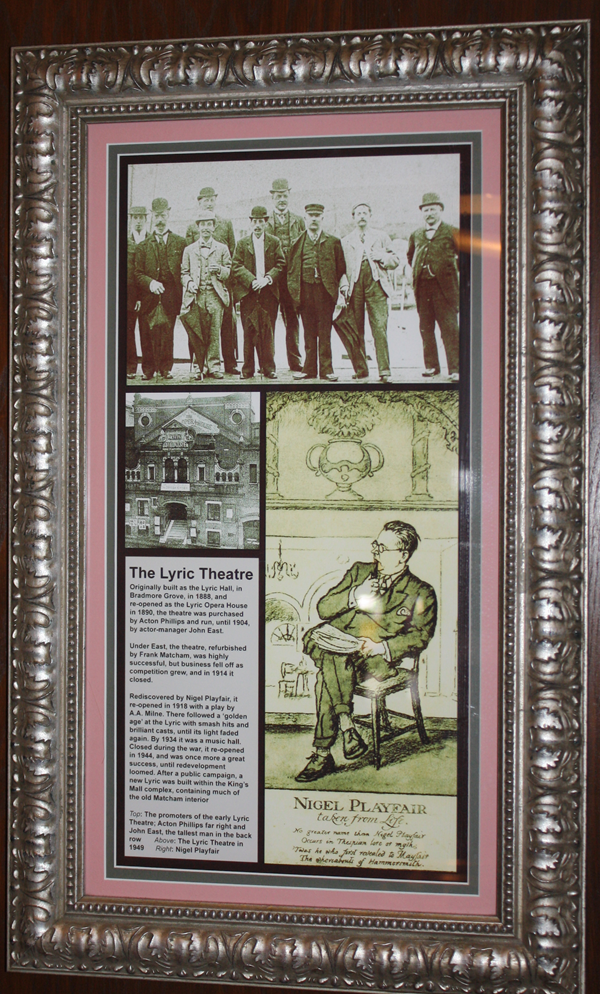

Framed illustration, photographs and text about The Lyric Theatre.

The text reads: Originally built as the Lyric Hall, in Bradmore Grove, ¡n 1888, and re-opened as the Lyric Opera House in 1890, the theatre was purchased by Acton Phillips and run, until 1904, by actor-manager John East.

Under East, the theatre, refurbished by Frank Matcham, was highly successful, but business fell off as competition grew, and in 1914 it closed.

Rediscovered by Nigel Playfair, it re-opened in 1918 with a play by A.A. Milne. There followed a ‘golden age’ at the Lyric with smash hits and brilliant casts, until its light faded again. By 1934 it was a music hall. Closed during the war, it re-opened in 1944, and was once more a great success, until redevelopment loomed. After a public campaign, a new Lyric was built within the King’s Mall complex, containing much of the old Matcham interior.

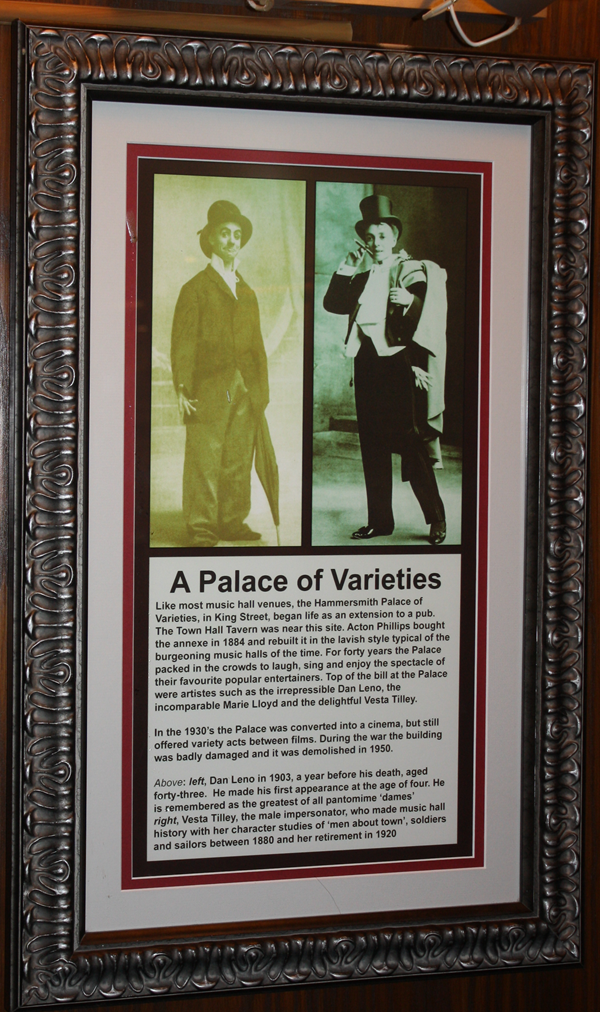

Framed photographs and text about The Hammersmith Palace of Varieties.

The text reads: Like most music hall venues, the Hammersmith Palace of Varieties, in King Street, began life as an extension to a pub. The Town Hall Tavern was near this site. Acton Phillips bought the annexe in 1884 and rebuilt it in the lavish style typical of the burgeoning music halls of the time. For forty years the Palace packed in the crowds to laugh, sing and enjoy the spectacle of their favourite popular entertainers. Top of the bill at the Palace were artistes such as the irrepressible Dan Leno, the incomparable Marie Lloyd and the delightful Vesta Tilley.

In the 1930’s the Palace was converted into a cinema, but still offered variety acts between films. During the war the building was badly damaged and it was demolished in 1950.

Above: left, Dan Leno in 1903, a year before his death, aged forty-three. He made his first appearance at the age of four. He is remembered as the greatest of all pantomime ‘dames’ right, Vesta Tilley, the male impersonator who made music hall history with her character studies of ‘men about town’, soldiers and sailors between 1880 and her retirement in 1920.

A framed photograph of Marie Lloyd.

The text reads: Mane Lloyd (real name Matilda Wood) became the foremost comedienne of her day with her saucy, but slightly poignant, cockney songs, such as ‘I’m one of the Ruins Cromwell knocked about a bit’ and My old man said Follow the Van. She died aged fifty-three in 1922

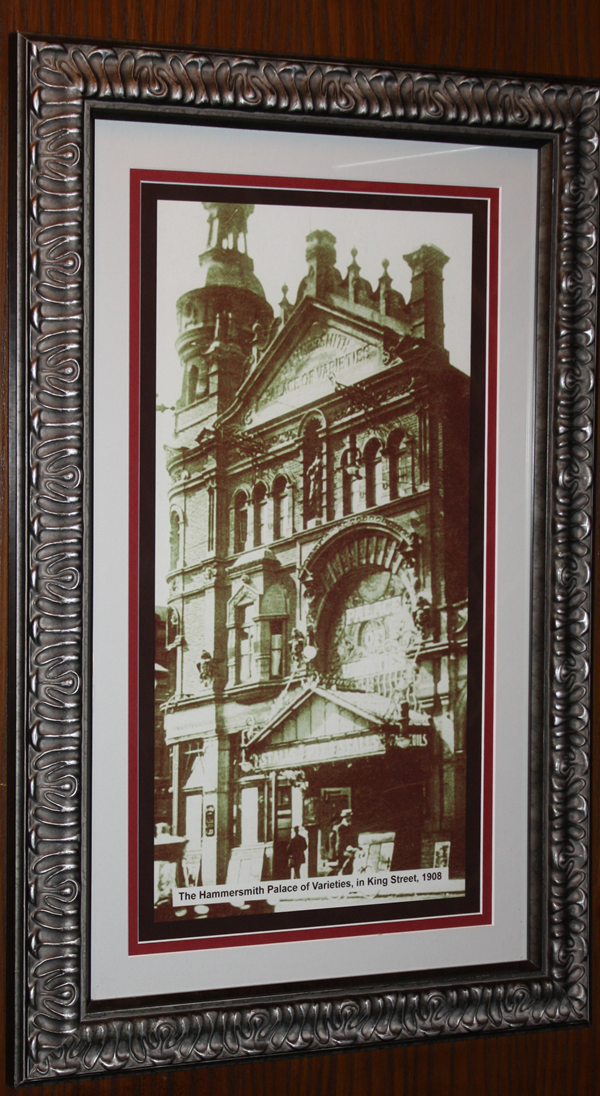

A framed photograph of The Hammersmith Palace of Varieties, in King Street, 1908.

A framed photograph of a horse-drawn bus outside The Swan on Hammersmith Broadway, 1894.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk